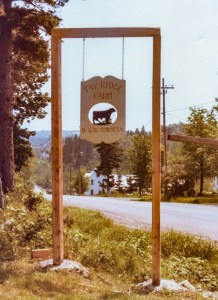

Many years ago in the seventies my wife and I were running a cattle farm located about twenty miles north of Fredericton, New Brunswick. This is the first in a series about our life on the farm

We eventually had about two hundred head of cattle with around 65 calves being born each year. The calves were typically born in February and March which as you might guess is a cold, snowy time in the part of Canada where we lived. For some reason, most calves like to be born at night.

Raising cattle is not the kind of thing where lots of help is available unless you have a a large family. Calving season is especially tough because it demands 24 hours a day attention. I would make two to three trips a night to our calving area which was in the woods around the second barn we built. It is hard to get out of a warm bed, suit up for the cold, and head outside not knowing what you would find.

The walk up the hill to the small field by the woods where the cattle were fenced was not a long one. Even with the walk back to the house it was only about six tenths of a mile. It seemed much longer in blowing snow especially since a good part of the walk went through the grove of tall spruce trees that separated our farm house from the barns.

Of course there were no street lights in the spruce forest. You had to go on that walk no matter what the weather. If I found a cow that had calved, I would walk the new calf to the barn between my legs and the new mother would follow. I would put the calf and cow in a stall filled with nice clean straw. Sometimes there would be more than one birth during a night. Depending on the weather the cow and calf would stay in the open front barn two to three days and then go back to join the herd. I had a larger pen in the barn where I could turn the cow and calve if things got crowded in the individual pens.

Once the cow and calf went back with herd, the calves had a special place for protection. The front part of the barn was arranged so that the calves could get under cover on dry straw during wet weather. With the barn facing south it made a nice place for them on a sunny day. Sometimes the straw looked like it was blanketed with calves. I remember looking over there one time and my oldest daughter who had just started school was sitting there in the sunshine in the middle of a dozen sleeping red and black Angus calves.

My relatives who were back in North Carolina asked me more than once if the walk in the dark scared me. I would always calmly tell them that walking through the dark woods in area most would call wilderness was safer than walking around Boston when I was in college.There was nothing in the woods that could harm me especially in the winter. All the bears and there were lots of them were hibernating. The moose were deep in the swamps and the rest of the critters were more afraid of me than I was of them.

There is one thing almost certain about the northern woods. When the temperature is down around minus twenty-eight Fahrenheit, there are no crazed muggers hiding in the three to four feet of snow in the spruce forest. They would be frozen like a Popsicle pretty quick.

The only good thing about calving season was that it was over in six to eight weeks. Getting the calves out of the snowy, wet weather was a good prescription for healthy calves. No one at the department of agriculture told us that this was the way we should raise calves. We figured it out ourselves. They also though that it was impossible to raise cattle using round bales. We put up over two hundred each year and proved that they worked. We could have used another barn for the bales but there was not a lot of money in cattle at the time.

In our ten years raising cattle, we never had a vet on the farm for a sick calf. I sometimes struggle to believe that myself and the fact that I cannot remember ever losing a calf. There were plenty of other adventures like the time a teenager on a motorbike chased a dozen heifers deep into the woods. It took most of the summer to get them back but that is a story for next time.