My seventy-seventh birthday is coming up in a few weeks. The thought of being that old has prompted a lot of introspection. Someimes we know why we do something but there are some forks in the road where our motivations might not be so clear. There are also things you remember which make you wonder how much influence they had on your decisions. I was in high school, a military one, when President Kennedy was assasinated. I remember the deaths of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. I also vividly remember the election of Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War demonstrations and the feeling of relief when I found out that I wasn’t going to get drafted to fight a war which I thought was wrong on more than one level. When I graduated college, I went back to the land on shores of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. Some dissatisfaction with the political direction in the United States helped direct me to the north in 1971.

I spent first weeks of 2026, entertaining myself with YouTube videos of the new generation of homesteaders. Many of them are young, and all that I have seen appear to be healthy enough to handle all the wood splitting required to live off grid. I often wonder how their lives might change a few years down the road when their families include two or three children who need educating while the unrelenting work taking care of farm animals demands much of their time. Some of these homesteaders seek purity and will not even consider using a chainsaw. Others seem to believe that doing everything with used equipment shows their dedication to a different kind of life with ingenuity and a dose of poverty. Some fully embrace ATVs, snowmobiles, tractors and even excavators. Most it not all of them embrace solar power. There is a propensity for them to have goats and chickens with few pigs and cattle sprinkled around. Some have subsistence permits and live off Alaska’s. bountiful salmon and wild game. No one seems to have the land to grow their own hay, but many are investing huge effort into growing vegetables in places were vegetables are very hard to grow. Some have very young children but very few have teenagers. I am sure there are many reasons why they are living off grid or in my world have gone back to the land. They will likely wrestle with their decisions as they get older. A few have figured out how absolutely brutal longterm homesteading is on the homesteaders. It will be interesting to see how many are still around five eyars from now.

Long before I graduated college in the summer of 1971, I wanted to move north There were all sorts of reasons but four years at military school along with four turbulent years at college set the stage. My freshman year (1967) at Harvard, I was one of three students out of 1,500 in our class from North Carolina. At the time North Carolina was a rural place, and I had grown up loving camping, fishing, and wandering the woods. No one from our family had ever been to college so there was no famial advice to lean on for a career. My single mother raised me by running a beauty shop in the back of our house. Her one piece of advice was whatever I chose to do, I should do it to the best of my ability. She had grown up on a mill pond with a father who was a miller. She had become the lady of the house for her five sisters and brother at the age of nine when her mother died in 1917 flu pandemic. She left home by her middle teenage years when her father remarried..

With those ties to the land and the family of one of mother’s sisters still farming, it was not a stretch for me to want to go back to the land and farm. A trip to Alaska and another to Nova Scotia fanned the flame. In the spring of 1971, I found an old farm on the Nova Scotia coast that was listed for $6,000. It included an old farm house and 140 acres with about thirty acres of that in a hayfield.

Restoring the old house, buying some farm equipment and a few cows are all part of my history. When we decided to get serious about farming we moved to New Brunswick where we built a farm where we eventually had sixty-five cows calving every year.

There were lots of other easier paths to take to adulthood. I needed a path that let me learn everything the hard way. I learned how to wire a house and do copper plumbing by reading Sears How-to-do-it pamplets. I learned to farm by reading books and listening to my neighbors in most cases. I built barns with just common sense, skill saws, and a chainsaw. We only left the farm when interest rates got to over 20%. We also made the decision three years after leaving the farm that we wanted our children to know their North Carolina based grandparents and hopefully find lives not far from us.

It was a huge effort to move from the farm to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I went to work for Apple. It took even more effort to move back to the states.

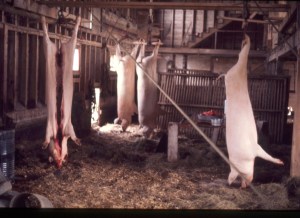

Now as I sit in my comfortable house eating food from local farms and exotic places like Trader Joe’s, I struggle to remember the day to day challenges we faced on the farm. I can remember all the wood splitting, the hauling it into the woodshed, the years of milking our Guernsey, Rosie. I also remember all those trips, often three times a night, to check for new born calves in the depths of winter. All the work that went into haying and gardening is clearly burned into my mind. The freezers were always filled with beef which is a luxury today. We had more garden produce than we could dream of eating but it was a lot of hard work especially when the black flies were around. We saw weather as cold as minus forty with sixty mile per hour winds and heat over one hundred degrees. We lived on the edge of civilization but most days we had power. We also had the equipment to move snow and take care of 200 head of cattle without hiring another person. There was a ten year stretch with no vacation. When we finally did get a vacation to Prince Edward Island, we did not know how to act on vacation. Farm life was brutally hard at times, often money was very short, but we all slept well at night.

Even with all the hard work, I would sign up for it again but with fewer cattle if somehow I miraculously got a body forty years younger. Whatever the reasons behind this generation going back to the land, it might well burn brightest in their memories like it does in mine.