The first time that I can remember facing an icy road, it was probaby 1961. I was a twelve-year old passenger in car headed back from Camp Raven Knob, a Boy Scout camp west of Mt. Airy, North Carolina. Adults had come to rescue us from another frozen, icy night in the three-sided Adirondack lean-tos. I wasn’t particularly worried about the icy roads because I wasn’t driving.

Seven years later I am home for the holidays from college and my mother is hosting a Christmas party in Mt. Airy, NC, for her extended family which are mostly from the next country over. Mount Airy is in the transition area between the hill country and the Blue Ridge Mountains. Weather forecasting in the sixties was a little more rudimentary and a snowstorm hit early in the afternoon. Snowstorms are not every day occurences in the North Carolina foothills. Our relatives were becoming worried about getting home. I was going to school in Massachusetts so my old Bronco had snow tires on all four wheels. I offered to escort a convoy through the worst hills. It might have been the first time I had driven in North Carolina snow which isn’t anything like northern snow. It is rare when NC snow isn’t slush or packed ice. That first trip was in slush which is no problem with snow tires. Everyone drove in my tracks and I took them half way home to the point there was hardly any snow on the road. I was young and probably didn’t worry about it very much.

There were many opportunities to drive on snowy roads during college. Four of us even took a trip to Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island in November our junior year. Cape Breton welcomed us with snow, sleet and freezing rain. We faced some very cold camping and tough driving in the old Bronco.

After graduating college, I moved to eastern Canada. Over the course of the next seventeen years I owned a variety of snow worthy vehicles from Land Rovers to Land Cruisers and 4WD trucks. We even had 4WD drive tractors on our 400 acres farmland.

My wife was in her orange rear wheel drive Volvo wagon on a very snowy day coming back from the doctor with our first child who had swallowed a bunch of Flintsone vitamins. The syrup of ipecac hadn’t worked at the doctor’s office. I had just found out when I came in from barn chores and rushed to the doctor’s office in my trusty 4WD Chevy pickup. I crested a hill as I was speeding to the clinic and there was my wife’s car stopped in the middle of the road. She had stopped because our daughter had started throwing up and she was afraid she would choke in her car seat. I didn’t have time to think, I avoided hitting my wife and daughter by putting the truck into a snow filled ditch. With the big snowbanks, I ended up safe, and I rode home with my wife, grabbed a tractor and a neighbor and we retrieved the truck without any problems.

Snowbanks along the rural roads were a great safety feature. You could slide into a snowbank without worrying about damaging your car. After we quit farming, I became a sales manager for the first Apple microcomputer dealer in the area. I had to travel to three locations in New Brunswick, one in PEI and another in Halifax, Nova Scotia. At first I did it in my old front wheel drive Subaru. One time I came home from a trip and was barely able to get the Subaru far enough in the driveway so I could get our tractor and snow blower around it.

Soon after that I switched to a rear wheel drive Volvo sedan. I put snow tires on all four wheels and fifty pounds of sand over each rear wheel in the trunk. I went everywhere in it. After I joined Apple, I once drove my sales manager from Toronto from Fredericton, New Brunswick to Charlottetown, PEI in a blizzard. He was amazed what the Volvo would go through and even more surprised at the ice encrusted ferry that we took to the island.

Four years later we are living on a mountainside overlooking Roanoke, Virginia. We bought an AWD Nissan our first winter there. We had a variety of AWD vehicles there from Subarus and Grand Cherokees to my wife’s AWD Volvo wagon and my AWD Acura MDX. The little Nissan Axcess was a favorite because I could put chains on all four wheels. There were storms when Little Limo as she was fondly known was the only safe way up and down our mountain. I ferried many people with groceries up and down the mountain to their parked cars at the foot of the hill over our seventeen years there. The Acura with its locking AWD mode was the second best vehicle on the mountain. It is still with us and now 21 years old.

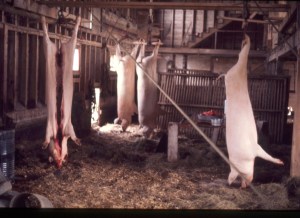

We lived on the NC coast for sixteen years and only had ice a few times. With no hills it is not much of challenge. Here in the Piedmont where we now live there are certainly enough hills to make things interesting but snow and ice is a rarity. Still in the last two weeks we have had two storms, one four inches of sleet and the other a foot of fluffy snow. We had no need to go out but I did go to our butcher shop located on the ice road pictured at the took. The Acura MDX never hesitated even a couple of really icy hills. It brought back some memories, even a snowy one to Newfoundland pictured below.